On July 9, 2019, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 5th Circuit will hear oral argument in Texas v. U.S., the next round of litigation challenging the Affordable Care Act (ACA). The appeals court is reviewing a federal trial court’s decision that the ACA’s minimum essential coverage provision (known as the individual mandate) is unconstitutional and, as a result, requires the entire ACA to be overturned. The individual mandate provides that most people must maintain a minimum level of health insurance coverage; those who do not do so must pay a financial penalty (known as the shared responsibility payment) to the IRS. The individual mandate was upheld as a constitutional exercise of Congress’ taxing power by a five member majority of the U.S. Supreme Court in NFIB v. Sebelius in 2012.

In the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA), Congress set the shared responsibility payment at zero dollars as of January 1, 2019. According to the Texas trial court, this action “compels the conclusion” that the individual mandate ceases to be a constitutional exercise of Congress’ taxing power because the associated financial penalty no longer “produces at least some revenue” for the federal government.1 The trial court went on to find that, because Congress called the individual mandate “essential” when enacting the ACA in 2010, the entire law must be invalidated. The trial court’s decision has not yet been implemented. However, if the decision does take effect, it will have complex and far-reaching consequences for the nation’s health care system, affecting nearly everyone in some way. A host of ACA provisions would be eliminated, including: protections for people with pre-existing conditions, subsidies to make individual health insurance more affordable, expanded eligibility for Medicaid, coverage of young adults up to age 26 under their parents’ insurance policies, coverage of preventive care with no patient cost-sharing, closing of the doughnut hole under Medicare’s drug benefit, and a series of tax increases to fund the new benefits.

This issue brief answers key questions about the case leading up to the oral argument on appeal.

Key Questions About the Texas v. U.S. Appeal

1. Who Is Challenging the ACA?

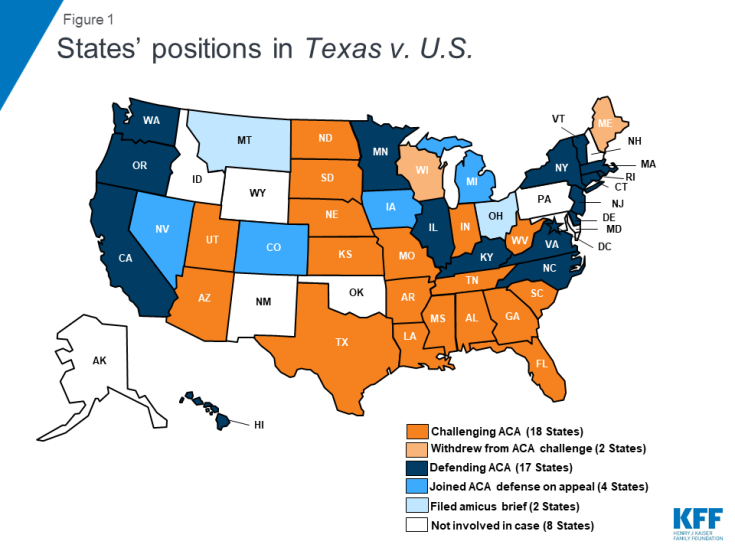

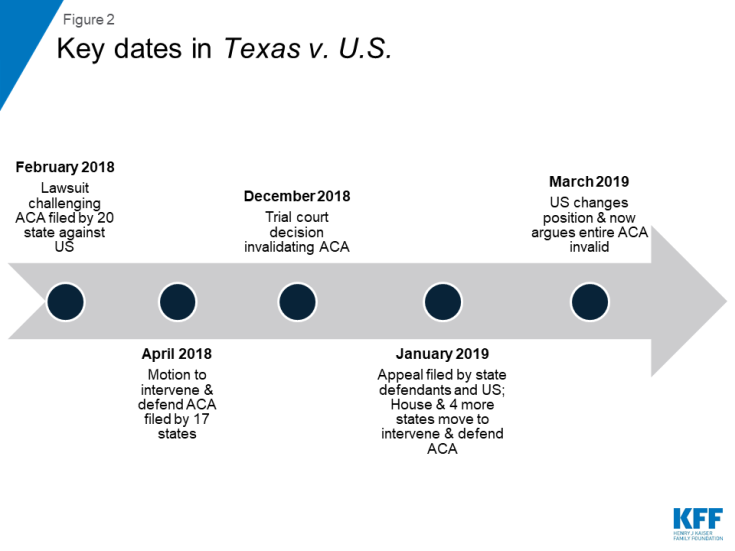

A group of 20 states, led by Texas, sued the federal government in February 2018, seeking to have the entire ACA declared unconstitutional (the “state plaintiffs”).2 The states are represented by 18 Republican attorneys general and 2 Republican governors. After Democratic victories in the 2018 mid-term elections, two of these states, Wisconsin and Maine, withdrew from the case in early 2019, leaving 18 states challenging the ACA on appeal (Figure 1).

In addition, two individuals joined the lawsuit in the trial court in April 2018, as plaintiffs challenging the ACA’s constitutionality.3 The individual plaintiffs are self-employed residents of Texas who claim that the individual mandate requires them to purchase health insurance that they otherwise would not buy, although there is no penalty if they fail to buy coverage.

2. What Is the Federal Government’s Position in the Case, and How Has It Changed Over Time?

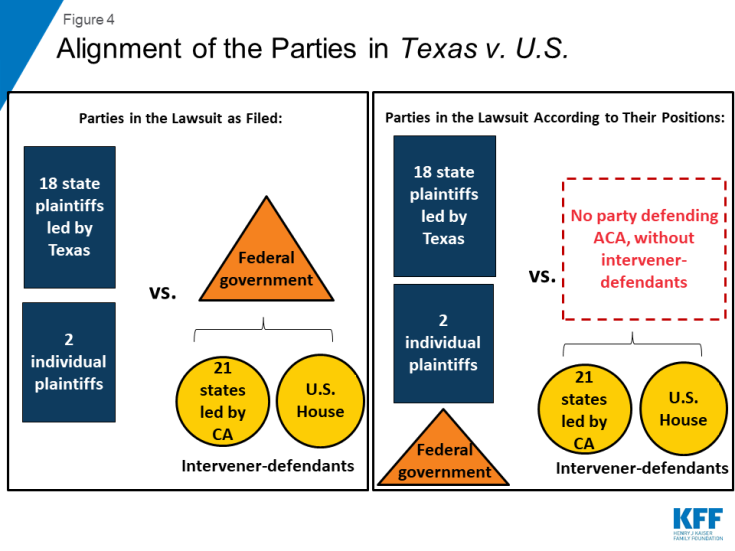

When the case was argued in the trial court, the federal government did not defend the constitutionality of the ACA’s individual mandate. Instead, the federal government agreed with the state and individual plaintiffs that the individual mandate is no longer constitutional under Congress’s taxing power as a result of the TCJA provision that set the financial penalty at zero.4 It is unusual for the federal government to take a position that does not seek to uphold a federal law.

However, unlike the plaintiffs, the federal government argued at the trial court level that only the ACA’s protections for people with pre-existing conditions, including guaranteed issue and community rating, should be struck down along with the individual mandate. The federal government took the position that these provisions cannot function effectively without the individual mandate but that the rest of the ACA should be allowed to survive.

Then, instead of filing its opening brief as a party seeking to overturn the trial court’s decision on appeal, the federal government instead informed the appeals court that it had changed its position. The federal government did not provide any reasoning to explain its March 2019 reversal. Instead, it stated that the “Department of Justice has determined that the district court’s judgment should be affirmed” and the “United States is not urging that any portion of the district court’s judgment be reversed.”5 In other words, the federal government was supporting the position that the entire ACA should be overturned. However, in its appeals brief, the federal government appeared to modify somewhat its position by asserting that some provisions in the ACA should survive the legal challenge. For example, the federal government identified “several criminal statutes used to prosecute individuals who defraud our healthcare system” that are part of the ACA and that the individual plaintiffs likely do not have standing to challenge.6 The federal government asserted that appeals court should allow the trial court to determine the scope of which ACA provisions should survive.

3. Who is Defending the ACA?

Another 17 states, led by California, were permitted by the trial court to intervene in the case and defend the ACA (the “state intervener-defendants”). These states are represented by Democratic attorneys general. They moved to intervene in April 2018, and the trial court granted their motion in May 2018 (Figure 2). Subsequently, in February 2019, the 5th Circuit allowed four more states to intervene in the case on appeal, bringing the total number of states defending the ACA in the case to 21 (Figure 1).7

The 5th Circuit also allowed the U.S. House of Representatives to intervene in the case to defend the ACA on appeal (Figure 2).8 However, as explained below, the court has asked for supplemental briefing which could indicate that the court may reconsider this decision.

4. What Issues Will the 5th Circuit Consider on Appeal?

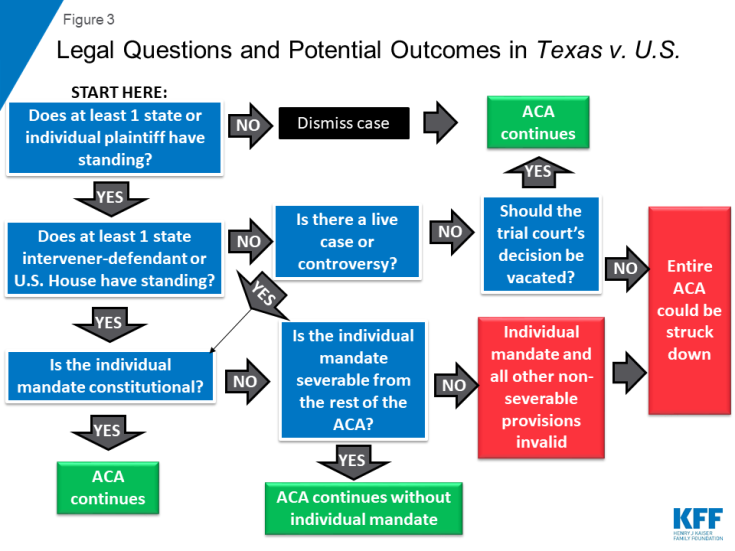

The 5th Circuit is not bound by the trial court’s decision interpreting the law and will consider the case anew on appeal. There are three main issues that the court may consider: (A) whether the parties have standing to invoke the court’s jurisdiction on appeal; (B) whether the ACA’s individual mandate, as amended by the TCJA, is constitutional; and (C) if the mandate is unconstitutional, whether it can be severed from the rest of the ACA, or on the other hand, whether other provisions of the ACA also must be invalidated. Figure 3 illustrates the legal questions and potential outcomes in the case.

(A) Do the Parties have Standing to invoke the court’s jurisdiction?

(1) Standing of the Individual Plaintiffs and State Plaintiffs to Challenge the ACA

At the outset, the court likely will consider whether the parties have standing to litigate the case. Standing ensures that federal courts are deciding actual cases or controversies as required by the U.S. Constitution. Standing is essential for the court to have jurisdiction to decide a case and therefore cannot be waived. To establish standing, a party must suffer an injury that is concrete and actual or imminent; fairly traceable to the challenged conduct; and likely to be redressed by a favorable court ruling. The trial court found that the individual plaintiffs satisfied the criteria to establish standing but did not analyze standing for the state plaintiffs. It is necessary that only one plaintiff have standing for a case to proceed.

The individual plaintiffs argue that they have standing to challenge the individual mandate because, even after Congress set the financial penalty for not complying at zero, they nevertheless feel compelled to comply with the federal law requiring them to maintain minimum essential coverage.9 The state intervener-defendants and the House assert that these plaintiffs are not harmed by the individual mandate because the ACA, as amended by the TCJA, merely “offers them a choice between purchasing insurance or doing nothing.”10 The state plaintiffs claim that the ACA’s individual mandate causes them to experience increased Medicaid and CHIP costs, due to increased enrollment, and increased administrative burden.11 The state intervener-defendants and the U.S. House respond that the state plaintiffs fail the standing test because their claims are “purely speculative” and/or unrelated to the individual mandate.12

(2) Standing of the State Intervener-Defendants and US House to Pursue an Appeal

On June 26, 2019, the 5th Circuit ordered supplemental briefing from the parties on three questions related to the standing of the state intervener-defendants and the House to pursue an appeal.13 The standing of the state intervener-defendants and/or the US House is particularly important in this case, since the federal government is not defending the ACA (Figure 4). It is hard to know what motivated the 5th Circuit to ask for supplemental briefing on the intervener-defendants’ standing in light of the Supreme Court’s June 17, 2019 decision in Va. House of Delegates v. Bethune-Hill14 or why the court may be reconsidering its earlier decision to allow the U.S. House to intervene. The 5th Circuit may be exercising extra caution in fully considering the standing issue because the Supreme Court’s decision was issued after briefing in Texas v. U.S. closed and a further appeal to the Supreme Court is likely in this case. This case is also unusual in that no party is defending the constitutionality of a federal law without the intervener-defendants, and the stakes are high if the entire ACA is struck down. Additionally, the court asked the parties to address whether intervention, particularly by the House, was timely. When granting the House’s January 2019 motion to intervene, the 5th Circuit found that it was “not untimely in the context of this case.”15

The court also asked whether a live case or controversy might still remain even if neither the state defendants nor the House has standing, given the federal government’s position on appeal.16 If both the state defendants and the House are dismissed from the appeal, there will not be any party defending the individual mandate’s constitutionality. The only area where the federal government is taking a different position from the state and individual plaintiffs is about whether some ACA provisions should survive if the mandate is unconstitutional. It remains to be seen whether the 5th Circuit would find that this constitutes a live case or controversy and allow the appeal to proceed, if the court reaches this point in the analysis.

Finally, the 5th Circuit asked how the case should be resolved if neither the state defendants nor the House has standing and the federal government’s change in position has mooted the appeal.17 If the 5th Circuit decides that the Texas v. U.S. appeal is moot, it could vacate the trial court’s judgment, allowing the ACA to survive, or allow the decision to stand, meaning the ACA would be struck down if the trial court goes on to issue injunctive relief to implement its decision.

(B) is the individual mandate constitutional after the tcja set the financial penalty at zero?

Next, the court will consider whether the individual mandate as amended by the TCJA is constitutional. The state and individual plaintiffs and the federal government all argue that the requirement to produce some revenue was “essential” to the Supreme Court’s finding that the individual mandate could be saved as a valid exercise of Congress’s power to tax.18 Without that feature, they assert that the mandate is a command to purchase health insurance, which as the Supreme Court held in in NFIB, is an unconstitutional exercise of Congress’ power to regulate interstate commerce.

The state intervener-defendants argue that the Supreme Court’s characterization of the individual mandate as “’establishing a condition – not owning health insurance – that triggers a tax’” still controls.19 In their view, the TCJA’s reduction of the tax amount to zero did not make the individual mandate unconstitutional but rather created a scenario in which the ACA now “may encourage Americans to buy health insurance, but it imposes no legal obligation to do so.”20 The House asserts that the TCJA amendment “confirms beyond doubt” that the individual mandate “is not a legal command to buy insurance because it removes any consequence for failing to” do so.21

(C) if the individual mandate is unconstitutional, is it severable from the rest of the aca?

If the court finds that the individual mandate is unconstitutional, it will then decide whether it can be severed from the rest of the ACA. The state and individual plaintiffs argue that the individual mandate is not severable from the rest of the ACA. They point out that the federal government has consistently taken the position that the mandate is essential to the proper functioning of the guaranteed issue and community rating provisions because it is needed to avoid adverse selection and throwing the individual market into a “death spiral.”22 They also argue that the mandate is inseverable from other “major provisions” of the ACA because the mandate was intended to offset the costs imposed by those provisions.23 And, they claim that the mandate is inseverable from the ACA’s “minor provisions” because “’[t]here is no reason to believe that Congress would have enacted them independently.’”24

The state defendants and the House argue that the individual mandate should be severed from the rest of the ACA if it is found unconstitutional. They point to the 2017 TCJA as “unambiguously establish[ing] that [Congress] intended the rest of the law to function in the absence of an enforceable mandate.”25 As a result, they assert that in this case, “we know for certain that Congress would have preferred ‘what is left’ of the Affordable Care Act to ‘no [Act] at all.’”26 When enacting the TCJA, Congress was aware of evidence from the Congressional Budget Office which projected that the guaranteed issue and community rating provisions could continue to function without an enforceable individual mandate. They also note that Congress rejected several attempts to repeal and replace the ACA in 2017.27

5. Who Else Has Weighed in on the Appeal?

In the 5th Circuit appeal, 2 more states (Ohio and Montana) filed an amicus brief arguing that the ACA’s individual mandate is unconstitutional but should be severed from the ACA, allowing the rest of the law to stand (Figure 1). The state’s amicus brief is one among nearly 25 others filed by a range of entities, including law professors; health plans; advocacy groups that represent seniors, women, people with disabilities, and people with chronic illnesses; health care provider associations; economic scholars; tribal nations; local governments; and other groups.

Looking Ahead

Oral argument is scheduled for 1:00 pm on July 9th, with 45 minutes to be shared among the state intervener-defendants and the House, and 45 minutes to be shared among the state plaintiffs, individual plaintiffs, and federal government. The case will be heard by a panel of three judges, including Judge Carolyn Dineen King (appointed by President Carter), Judge Jennifer Walker Elrod (appointed by President George W. Bush), and Judge Kurt D. Engelhardt (appointed by President Trump). There is no deadline by which the court must issue a decision, but it could come as early as fall 2019.

If the court finds that the individual mandate is unconstitutional and invalidates only that provision, the practical result will be essentially the same as the ACA exists today, as amended by the TCJA, without an enforceable mandate. If the court adopts the position that the federal government took during the trial court proceedings and invalidates the individual mandate as well as the protections for people with pre-existing conditions, then federal funding for premium subsidies and the Medicaid expansion would stand, and it would be up to states whether to reinstate the insurance protections.

The most far-reaching consequences, affecting nearly every American in some way, will occur if the court decides that the entire ACA must be overturned. The number of non-elderly individuals who are uninsured decreased by 19.1 million from 2010 to 2017, as the ACA went into effect. The ACA made significant changes to the individual insurance market, including requiring protections for people with pre-existing conditions, creating insurance marketplaces, and authorizing premium subsidies for people with low and modest incomes. The ACA also made other sweeping changes throughout the health care system including expanding Medicaid eligibility for low-income adults; requiring private insurance, Medicare, and Medicaid expansion coverage of preventive services with no cost sharing; phasing out the Medicare prescription drug “doughnut hole” coverage gap; reducing the growth of Medicare payments to health care providers and insurers; establishing new national initiatives to promote public health, care quality, and delivery system reforms; and authorizing a variety of tax increases to finance these changes. All of these provisions could be overturned if the trial court’s decision is upheld, and it would be enormously complex to disentangle them from the overall health care system.

Despite the trial court’s decision that the entire ACA should be invalidated, that decision has not yet been implemented, and the Trump Administration has indicated that it intends to continue enforcing the ACA while the appeal is pending. After the 5th Circuit issues its decision, one or more parties may ask the Supreme Court to review the case. Nearly 10 years after its enactment, the only certainty for the ACA in the foreseeable future is that there is once again uncertainty about its ultimate survival.